In the intricate and ever-evolving world of global commerce, supply chain management stands as the backbone of nearly every business that produces, moves, or sells physical goods. It is a complex discipline, a dynamic interplay of processes, technologies, and strategies aimed at delivering the right product to the right place at the right time, and in the most efficient manner possible. However, achieving this “perfect order” is not a simple, linear process. At its very core, supply chain management is a continuous series of balancing acts, a discipline defined by concessions and compromises. These are the trade-offs in logistics and supply chain management, the critical decisions that every business must make to align its operational capabilities with its strategic goals.

Understanding and mastering these trade-offs is not merely an academic exercise; it is fundamental to survival and success in the competitive marketplace. Every choice made—from selecting a supplier in a distant country to deciding on the packaging for the final product—involves evaluating competing objectives. Should a company prioritize speed of delivery to enhance customer satisfaction, even if it means incurring significantly higher transportation costs? Should it maintain vast amounts of inventory to prevent stock-outs, at the risk of tying up capital and increasing holding expenses? These questions rarely have a single, universally correct answer. The optimal solution is always contingent on a company’s specific context, its industry, its customer expectations, and its overall business strategy. The ability to astutely evaluate the trade off value—the perceived worth of choosing one option over its alternative—is what separates market leaders from their competitors. It’s about making informed, strategic decisions rather than simply reacting to operational pressures. This article delves deep into the most critical trade-offs that define modern logistics and supply chain management, exploring the nuances of each decision and providing a framework for navigating these complex choices to build a resilient, efficient, and competitive supply chain. We will explore foundational logistics choices, strategic dilemmas, and even complex socio-economic ideas like the equity efficiency trade off example as it applies to global operations.

The most classic and pervasive trade-off in all of logistics is the tension between total cost and the level of service provided. At a high level, it seems simple: better service costs more. Faster delivery, higher product availability, and more flexible return policies all come with a price tag. The challenge for any company is to find the “sweet spot”—the point at which the service level meets or slightly exceeds customer expectations without inflating costs to an unsustainable degree. This isn’t a single decision but a cascade of choices across the supply chain.

The most direct manifestation of the cost-service trade-off is in transportation. The choice between shipping modes is a primary example, but the trade-off extends beyond just the mode to include reliability and flexibility.

Air Freight: This is the fastest option, capable of moving goods across continents in a matter of hours or days. This speed translates into a high level of service, enabling businesses to respond quickly to market demands, replenish stock rapidly, and meet tight deadlines. However, it is by far the most expensive mode of transport, often costing 5 to 10 times more than ocean freight. It is typically reserved for high-value, low-volume goods (like the latest consumer electronics), lightweight items where freight is not the dominant cost, or urgent shipments where the cost of a stock-out would be catastrophic. For businesses that compete on speed, the high cost of air freight is a necessary investment.

Sea Freight: The workhorse of global trade, sea freight is the most cost-effective way to move large quantities of goods over long distances. This makes it the default choice for most importers and exporters, especially for bulk commodities, raw materials, and large consumer goods. The trade-off is time and variability. A shipment from China to the United States can take anywhere from 20 to 40 days, and this timeframe can be affected by weather, port congestion, and customs delays. This long lead time necessitates higher inventory levels, more sophisticated demand forecasting, and a greater risk of stock-outs if there are unforeseen delays. Companies must decide if the significant cost savings are worth the reduced flexibility and increased inventory holding costs. A critical part of this decision involves understanding the nuances of container shipping, and for many, a key resource is learning about the difference between FCL and LCL container shipping, which allows for better cost management based on shipment volume.

Land Freight (Truck and Rail): For domestic or continental shipping, the trade-off continues. Full Truckload (FTL) shipping is generally faster and safer for large shipments, as the truck goes directly from origin to destination. Less than Truckload (LTL) is more cost-effective for smaller shipments but involves multiple stops, longer transit times, and a higher risk of damage. Rail is often cheaper than trucking for very long distances but is typically slower and less flexible, often used for the long-haul portion of an intermodal journey.

Intermodal Transportation: A sophisticated approach is to blend these modes. For instance, a “sea-air” service might involve shipping goods by ocean from a factory in China to a hub like Dubai or Los Angeles, then transferring them to an airplane for the final leg of the journey. This creates a balanced trade off value, offering a service that is faster than pure ocean freight but significantly cheaper than pure air freight. This hybrid model is an excellent strategy for products with moderate demand uncertainty and a need for reasonable speed.

Finding the right balance requires a deep understanding of customer needs and product characteristics. Do customers demand two-day shipping, or are they willing to wait a week for a lower price? Is the product a stable commodity or a seasonal fashion item? The answer dictates the optimal transportation mix. Often, the cheapest way to import from China is not a single method but a blended, dynamic strategy that uses different modes for different products or stages of the product lifecycle.

Another critical dimension of the cost-service trade-off is inventory management. The goal of inventory is to have products available when and where customers want them. High product availability is a cornerstone of good customer service. However, inventory is not free; it represents a significant, and often underestimated, cost to the business.

Deconstructing Inventory Holding Costs: These are the explicit and implicit costs of storing goods.

Capital Costs: The money tied up in inventory could have been invested elsewhere—in marketing, R&D, or even earning interest. This opportunity cost is often the largest component of holding costs, typically calculated using the company’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

Storage Space Costs: This includes rent for warehouse space, utilities (heating, lighting), material handling equipment, and the labor required to manage and move the inventory.

Service Costs: This covers insurance to protect against loss or damage and any taxes levied on the value of the inventory held in a warehouse.

Risk Costs: This is perhaps the most significant and variable component. It includes the cost of obsolescence (products becoming outdated, especially in tech and fashion), damage during handling, theft (shrinkage), and devaluation due to market changes.

To minimize these costs, businesses strive to keep inventory levels as low as possible. This is the principle behind Just-in-Time (JIT) manufacturing. However, low inventory levels increase the risk of a stock-out—not having a product on hand to meet customer demand. The cost of a stock-out can be severe, including lost sales, a damaged reputation, and the potential loss of a customer for life. Therefore, companies must make a strategic trade-off. This is a clear example of trade off in economics applied to operational strategy.

Postponement as a Strategy: A powerful technique for managing this trade-off is postponement. This involves delaying the final configuration of a product for as long as possible. For example, a computer manufacturer might produce a large batch of “vanilla” base units and only install the specific RAM, hard drive, and software once a customer order is received. This allows them to hold inventory in a more generic, less-risk form, reducing the risk of obsolescence while still offering a wide variety of customized options to the customer. This is a key strategy for balancing customization and inventory cost.

Beyond the foundational, day-to-day operational decisions, a set of more strategic trade-offs shapes the very design and nature of a company’s supply chain. These choices have long-term implications and are deeply intertwined with the company’s competitive strategy.

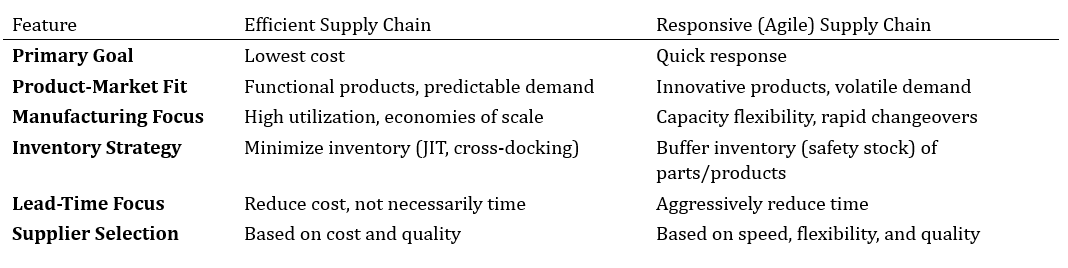

This is arguably the most important strategic trade-off. It dictates whether a supply chain is built primarily for low cost or for speed and agility.

Efficient Supply Chains: These are focused on producing and delivering goods at the lowest possible cost. They are the domain of operational excellence, characterized by economies of scale in production, high asset utilization, minimized inventory levels, and a relentless focus on cost-effective transportation. Companies like Walmart have historically built their success on hyper-efficient supply chains, leveraging their massive scale to drive down prices for consumers. The trade-off is a lack of flexibility. Efficient supply chains are designed for stable, predictable demand and can be brittle when faced with sudden shocks.

Responsive (or Agile) Supply Chains: These are designed to respond quickly to changing market demands. They prioritize speed, flexibility, and the ability to handle uncertainty and variety. Key features include holding safety stock of key components, investing in rapid transportation, and having a network of smaller, decentralized warehouses located closer to customers. Companies in the fast-fashion industry or the volatile world of consumer electronics, which must adapt to the latest consumer electronics industry trends in 2025, rely on responsive supply chains. They accept higher costs in production and logistics as the price of being able to capture fleeting market opportunities and avoid the massive cost of obsolescence.

The choice is not binary. Most companies need a blend of both, often creating a “hybrid” strategy where they use an efficient supply chain for their high-volume, predictable core products and a responsive supply chain for their new, innovative, or high-variability products. This is where a deep understanding of risk management in sourcing becomes critical.

Directly linked to the efficiency vs. responsiveness trade-off is the question of product variety.

Standardization: Offering a limited range of products with few variations has immense supply chain benefits. It allows for longer production runs, which lowers manufacturing costs per unit. It simplifies forecasting, reduces the number of SKUs (Stock Keeping Units) to manage, and allows for bulk purchasing of raw materials. This is the path to maximum efficiency.

Customization: Offering customers a wide array of choices—different colors, sizes, features—can be a powerful competitive advantage. However, it introduces significant complexity and cost into the supply chain. It requires more complex forecasting (at the individual SKU level), shorter production runs, and higher inventory levels to support all the possible variations. This is a strategy that requires responsiveness.

This is a classic trade-off where many companies find a middle ground. For example, the auto industry often uses a platform strategy, where many different models are built on the same underlying chassis and use the same core components, but offer extensive customization in terms of trim, color, and optional features. When sourcing manufactured goods, this trade-off is central to the conversation. Businesses must decide whether they are pursuing an ODM (Original Design Manufacturing) model, where they select a standardized product from a factory’s existing catalog, or an OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturing) model, where they provide a custom design. Understanding the difference between OEM and ODM manufacturing is crucial for any importer. If pursuing customization, it becomes paramount to also consider how to protect your product idea when you outsource from China.

For decades, the dominant trend was globalization—sourcing products and materials from wherever in the world they could be produced for the lowest cost. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent geopolitical shifts exposed the risks of long, complex global supply chains. This has led to a major re-evaluation.

Globalization (Offshoring): The primary benefit is lower cost, particularly lower labor costs. Sourcing from manufacturing powerhouses like China also provides access to massive scale, specialized expertise, and a vast network of suppliers. The drawbacks are now much clearer: long lead times, vulnerability to disruptions, and reduced control. This makes services like third party quality control not just a good idea, but an essential part of the process.

Localization (Nearshoring/Reshoring): This involves moving production closer to the end market. The benefits are the mirror image of globalization’s weaknesses: shorter lead times, lower risk, and greater control. The trade-off is, once again, cost. A more sophisticated way to evaluate this is through a Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) analysis. TCO goes beyond the factory gate price and includes all costs: freight, duties, inventory, quality-related costs, travel, and a quantified risk factor. When viewed through a TCO lens, the cost advantage of offshoring can sometimes shrink or disappear entirely. The emerging solution for many is a “China + 1” strategy, which maintains a core manufacturing base in China for its efficiency while developing a secondary source in another country to diversify risk. This is a sophisticated way to manage the trade off value between cost and resilience. Understanding the landscape of key manufacturing hubs of China remains crucial even in a diversification strategy.

While logisticians often focus on cost and speed, the decisions they make have broader economic and social implications. This brings us to a concept borrowed from economics: the equity-efficiency trade-off. In classic economics, this describes the idea that policies aimed at creating a fairer distribution of wealth (equity) can sometimes reduce overall economic output (efficiency), and vice-versa. A classic example of trade off in economics is progressive taxation: it aims for greater equity by taxing the rich more, but critics argue it can reduce the incentive to work and invest, thus lowering overall economic efficiency.

How does this trade off between equity and efficiency example apply to a supply chain? We can reframe “efficiency” as actions that maximize the company’s profit and minimize its costs. We can define “equity” as actions that create fairer outcomes for stakeholders, including customers, suppliers, and workers.

Efficiency-Focused Decisions:

- Centralized Distribution: Building one or two massive, highly automated distribution centers to serve an entire country is incredibly efficient. It minimizes overhead and maximizes economies of scale.

- Aggressive Procurement: Squeezing suppliers for the lowest possible price, demanding long payment terms, and holding minimal inventory of their components reduces direct costs.

- Labor Arbitrage: Moving production to the country with the lowest possible labor costs.

Equity-Focused Decisions:

- Decentralized Distribution: Maintaining a network of smaller, regional warehouses ensures that customers in remote or less populous areas receive their orders just as quickly as those in major cities. This provides greater “equity of service” but is far less efficient.

- Ethical Procurement: Partnering with suppliers and paying them a fair price that allows them to invest in their own businesses and pay their workers a living wage. This involves effective supplier relationship management, which can lead to better quality and reliability in the long run, but may increase short-term costs.

- Sustainable Sourcing: Choosing suppliers who adhere to strong environmental and labor standards (ESG compliance). This commitment to sustainable sourcing in supply chain management can be a powerful brand differentiator but often involves higher-cost materials and processes.

An excellent equity efficiency trade off example in a supply chain context is a large e-commerce company’s delivery promise. Promising free, two-day shipping to every single customer in a country is a move towards high equity—everyone gets the same great service. However, it is wildly inefficient. The cost to serve a rural customer is exponentially higher than the cost to serve a customer in a dense urban center. An efficiency-first approach would involve charging for shipping based on distance or offering slower, cheaper options for less profitable areas. The modern consumer, however, has been trained to expect high equity of service, forcing companies to absorb these inefficiencies.

Given these complex and often conflicting objectives, how can a business make the right choices? The answer lies in a combination of smart strategy, effective partnerships, and modern technology. Trade-offs never disappear entirely, but they can be managed more effectively, shifting the “efficiency frontier” outwards.

Technology is the great enabler. Modern supply chain management systems provide a level of visibility and data that was unimaginable just a decade ago.

Advanced Analytics and AI: By analyzing historical sales data, market trends, and even external factors like weather patterns, AI-powered forecasting tools can predict demand with much greater accuracy. This allows companies to optimize inventory levels, reducing holding costs without increasing the risk of stock-outs. AI is also revolutionizing procurement, as detailed in case studies of artificial intelligence in procurement.

Transportation Management Systems (TMS): A TMS can analyze thousands of potential shipping routes and carrier options in real-time to find the optimal balance of cost and speed for each individual shipment, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all approach.

Warehouse Management Systems (WMS): A WMS optimizes the storage and retrieval of goods within a warehouse, managing the trade-off between dense storage (efficiency) and ease of access (responsiveness).

Digital Twins: This is a cutting-edge technology where a complete virtual replica of a physical supply chain is created. This “digital twin” can be used to simulate the effects of various decisions. A company could model the impact of closing a distribution center or shifting from ocean to air freight, seeing the full effect on costs, service levels, and inventory before making a single real-world change.

Blockchain and Traceability: For companies concerned with sustainability and ethical sourcing, blockchain offers a way to create an immutable record of a product’s journey from raw material to finished good. This enhances supply chain traceability, giving both the company and the consumer confidence in the product’s origins.

For businesses sourcing from overseas, particularly from a market as vast and complex as China, navigating these trade-offs alone can be daunting. A sourcing partner is not just a transactional intermediary; they are a vital part of managing the trade-offs.

Supplier Selection and Negotiation: An experienced agent can identify reliable suppliers who offer the best trade off value between cost and quality. They can vet factories, conduct audits, and negotiate better prices and terms. They help answer the crucial question: Can I trust Alibaba verified supplier by providing on-the-ground verification. They can also help negotiate lower Minimum Order Quantities (MOQs), a critical step for smaller businesses, as detailed in our guide on how to negotiate lower MOQ.

Quality Control: One of the biggest trade-offs in global sourcing is risking lower quality for a lower price. An agent mitigates this risk by implementing a robust inspection and quality control in manufacturing program. This involves pre-production, in-line, and final inspections to ensure products meet standards before shipment. Understanding the importance of this step is why we emphasize China factory audits.

Logistics and Payment: A sourcing agent can manage the complex logistics of moving goods from the factory to the port and onto a vessel. They can help choose the best shipping method, find cost-effective freight forwarders, and handle documentation. They can also provide guidance on secure payment methods, a topic we cover in our review of the best online payment processors for small business.

Risk Mitigation: Whether it’s navigating cultural nuances, protecting intellectual property, or understanding local regulations, a sourcing agent acts as a risk buffer. They provide the local knowledge and presence needed to manage the inherent risks of global sourcing.

By leveraging the expertise of a partner like Maple Sourcing, businesses can make more informed decisions. They gain access to the cost benefits of sourcing from China while simultaneously managing the trade-offs related to quality, risk, and logistics. It transforms a series of difficult choices into a managed, strategic process. You can learn more about our comprehensive sourcing services on our website.

The landscape of logistics and supply chain management is not one of absolute right and wrong answers, but of carefully weighed examples of trade offs. The pursuit of a “perfect” supply chain—one that is simultaneously the cheapest, the fastest, and the most flexible—is a futile one. The true goal is to build a supply chain that is perfectly aligned with a company’s specific business strategy and the expectations of its customers.

The key is to recognize that every decision, from choosing a supplier to selecting a shipping container, involves a compromise. The fundamental tension between cost and service permeates every choice. Strategic dilemmas like efficiency versus responsiveness, globalization versus localization, and standardization versus customization define the long-term resilience and competitiveness of a business. And deeper, more complex issues, such as the equity efficiency trade off example, are forcing companies to consider their wider social and environmental responsibilities as part of their operational strategy.

There is no magic formula for resolving these trade-offs. The optimal balance for a low-cost retailer will be vastly different from that of a luxury brand or a life-saving medical device company. Success lies not in eliminating trade-offs, but in understanding them, quantifying them, and managing them intelligently. It requires a clear strategy, robust data, powerful technology, and often, the right partners. By embracing the art of the balanced supply chain, businesses can navigate the complexities of global commerce, turning a series of difficult choices into a sustainable competitive advantage. It is in the masterful management of these trade-offs that true supply chain excellence is found.